what

I distill the

natural world.

For several years, I only took photos of birds. I loved the simplicity of the long lens: zoomed in, birds that could fit in the palm of your hand loom, removed of context and scale, before a background so blurred you wouldn't know Canada from Costa Rica.

And I made plenty of photographs of which I'm still proud. But, in that intense singlemindedness, I was missing something.

I became obsessed with finding new birds, spent full days hyper-focused, head on a swivel, ears ajar. My attitude towards nature changed; a walk in the woods without looking for birds was a walk wasted.

I had inadvertently linked the success of a day outside to the number of birds I had photographed. I could no longer enjoy the outdoors independent of the birds I saw or whether the day's images were sharp and well-lit. I stayed inside on plenty of beautiful days, solely because the sun was too bright or the wind prevented the birds from perching.

My bird fixation was distracting me, preventing me from appreciating what was under my nose. I was contradicting the reason I picked up a camera all those years ago: I wanted to slow down, to learn to more clearly see and feel in the natural world.

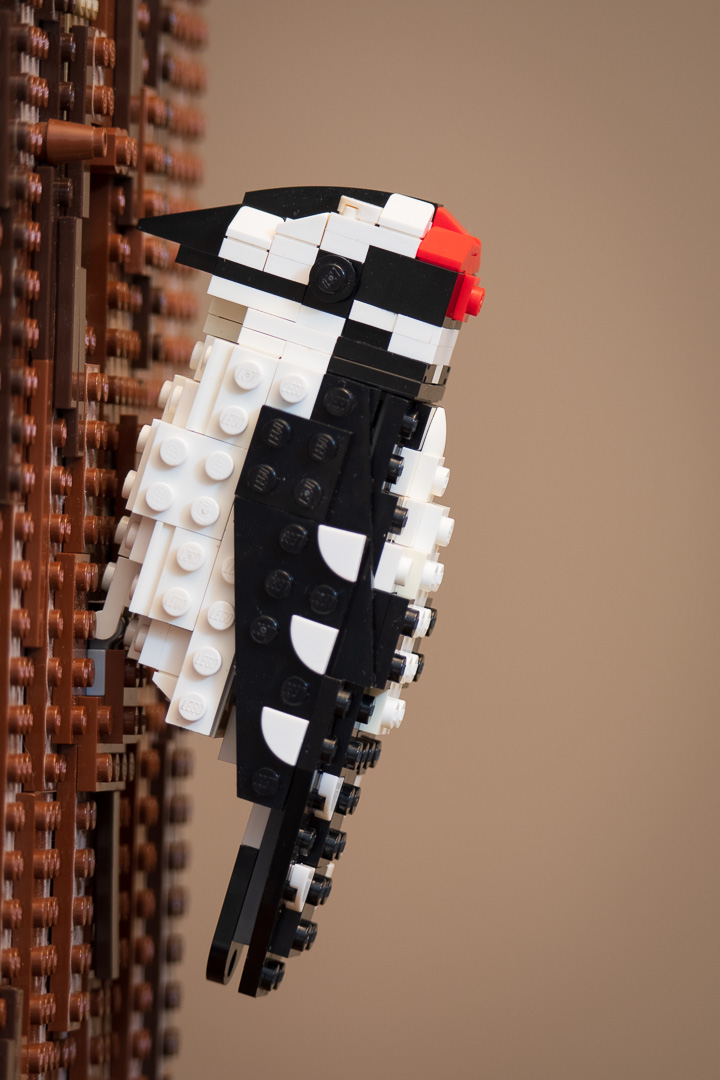

That's not to say I hate birds, or even that I never include them in my images. They're still a vital part of my environment.

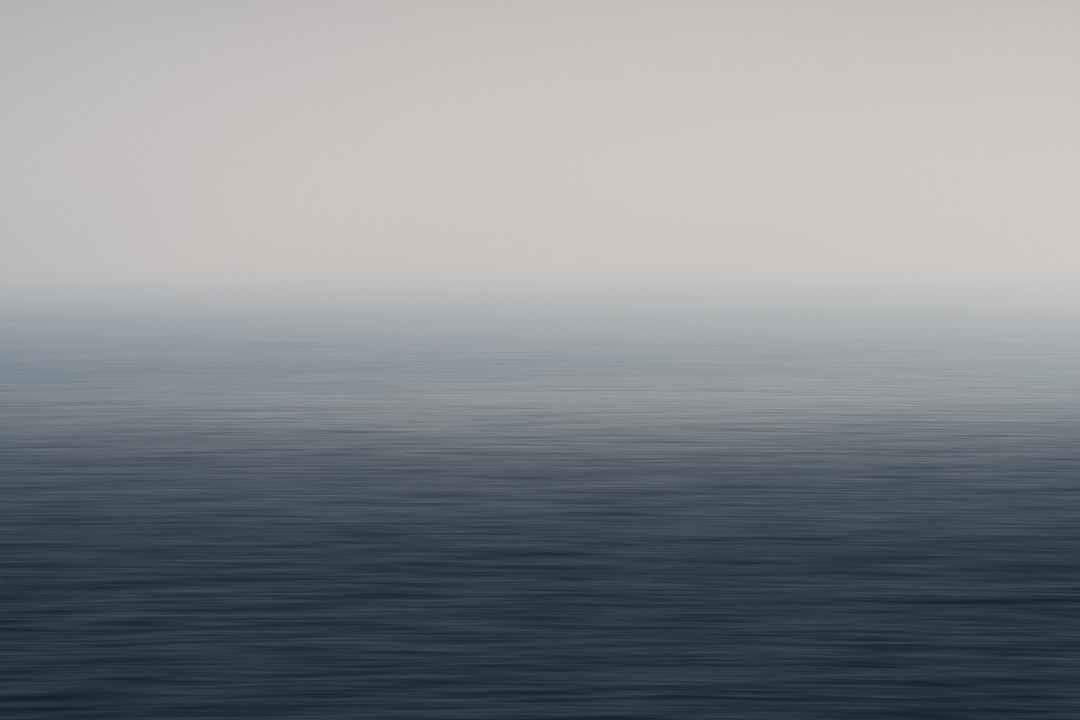

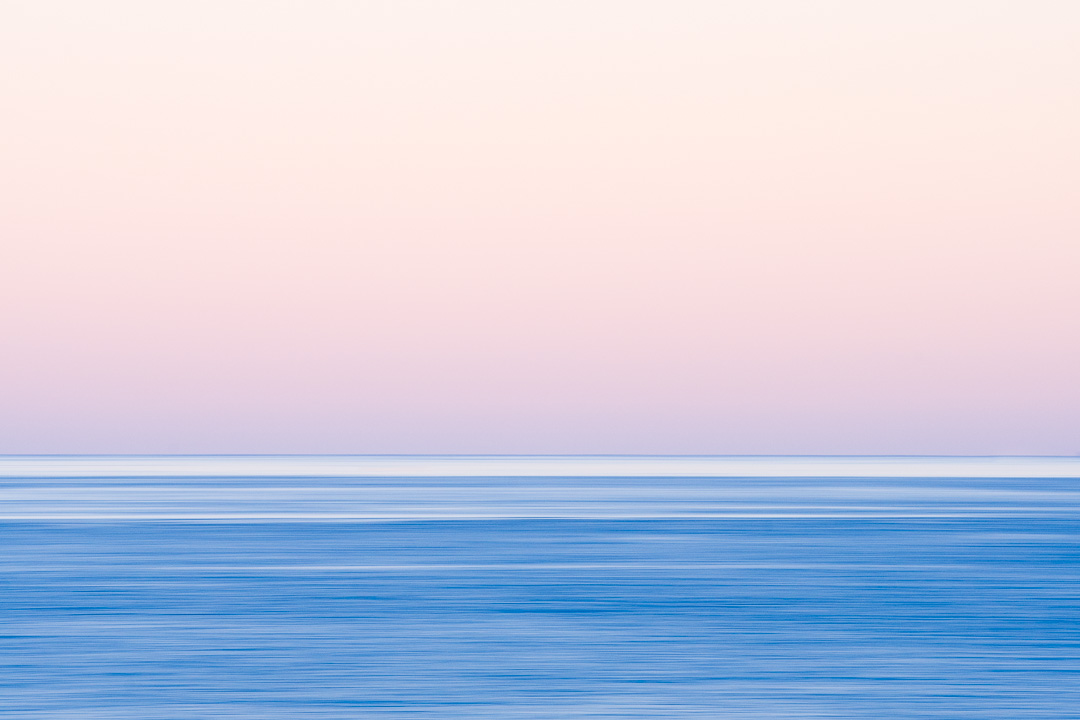

However, my focus has changed. Rather than capture objectively, I seek out the feelings that compel me outside before dawn and keep me there long after dark.

Looking down a long lens at a little bird, the world is small. Only one tiny slice is visible, and most of it is blurred and compressed. By taking a step back, I see more, feel more.

In my newer work, birds are, like everything else, a vessel for feeling. They may draw the eye, but they are rarely the subject, only an extra dash of pepper flakes in an already spicy world.

In wildlife photography, the subject is obvious. It's even in the name. The subjects of these images, however, are more ambiguous. The sky? The dusk?

Even a simple photograph of the moon isn't really about the moon. Its purpose is not to remind the viewer of the shape of the moon or that yes, they think they've seen that buttery orb before. It's a tone-moment, a vignette of feeling, a distillation of the aggregate natural world.

Even now, after years of practice, I still have trouble slowing down and stepping back from the viewfinder. As obvious as it sounds, the first step of capturing a feeling is noticing that feeling, and that only comes with patience and open eyes.

I know, now, that capturing ambiance is not objective or routine. There is no procedure to capture a feeling. I can't rely on what has worked in the past; each new photograph is the product of trial and error and unbound intuition.

I'm not sure what compels me towards minimalism, but I think it has something to do with steam on a mirror, each simple composition wiping at the glass, revealing another glimpse of the essence beyond. Perhaps one day, I will capture the essence of the world in its true, simplest form, and the glass will be wiped fully clean. Until then, I'll savor those glimpses.